|

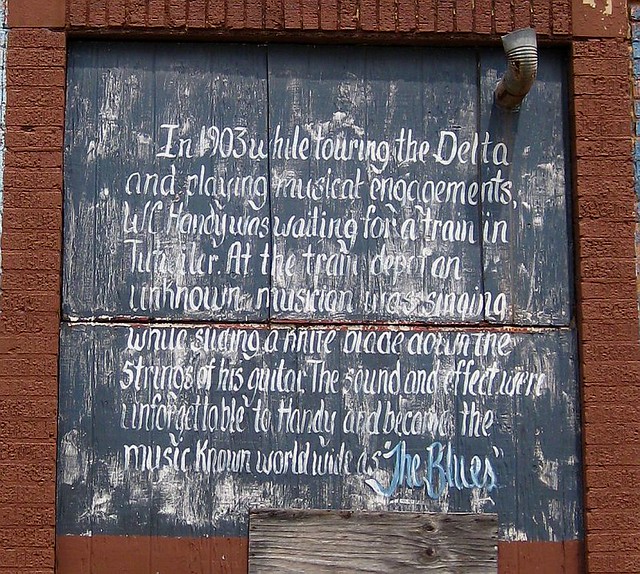

| From a mural at the old train station in Tutwiler, Mississippi |

In In Search of the Blues, Marybeth Hamilton goes looking for what she calls "the authentic origins of the blues" and comes back with some interesting conclusions. Describing her thoughts upon looking at a photograph she'd taken during her trip through the Mississippi Delta, she says "Every landscape is a work of the mind, shaped by the memories and obsessions of its observers." Replace the word 'landscape' with 'song' and that one sentence pretty much sums up the gist of her book, as she goes on to discuss how the blues was not shaped so much by the musicians who played it as it was by the white people who sold it then, later, studied it and, later still, revived it. From the record label talent scouts of the 20s and 30s, to Alan Lomax in the 40s, aficionados such as James McKlune in the 50s, John Fahey and Brit rockers like the Rolling Stones and Eric Clapton in the 60s, and even, I would add, all the way up through the early 2000s and Jack White's determination with the White Stripes to "trick teenaged girls into singing Son House"-- It has been people like these who've shaped what the term "blues music" brings to mind.

While the true roots of the blues are generally considered vague and undetermined, its earliest popular incarnation was embodied by full band-accompanied performers singing well-crafted and sophisticated numbers. Women such as Ma Rainey, Bessie Smith, and Mamie Smith were considered the queens of blues music. Band leader W.C. Handy claims to have discovered the blues, but his interpretations of it bear no more resemblance to the genre's current definition than what was crooned by the queens. And even within the commonly recognized genre, there's variety. The early Mississippi Delta/country blues of Charley Patton, Son House, and Robert Johnson migrated north to become the electrified Chicago blues of Muddy Waters and B.B. King, which were eventually usurped by the white boy blues of musicians like Stevie Ray Vaughan and Charlie Musselwhite. It goes on and on. Jazzmen such as Jelly Roll Morton even traced a strong connection to the blues, tangling the skein even further. What it all really boils down to, if you look at it objectively, is that defining what the blues is and what its effects are becomes a highly subjective and personal thing.

My own preferences in blues music were originally inspired by and continue to be influenced by Jack White. A quick look through the blues tunes he's covered reveals an extensive knowledge of the genre-- He's run a gamut through the Mississippi Sheiks, Charlie Jordan, Howlin' Wolf, Muddy Waters, John Lee Hooker, Tampa Red, Tommy Johnson, Blind Willie McTell, Blind Willie Johnson... But it's obvious that he's got a special reverence for the old Mississippi Delta guys such as Johnson, Patton, and, most of all, Son House. What is it about that particular style of blues that he so loves? From what he's said in interviews and how he's crafted his own music, it would seem to be something along the lines of how Hamilton described the singing of these musicians in In Search of the Blues-- '... it was "rough, spontaneous, crude and unfinished," dominated by "stark, unrelieved emotion"...' Even the most polished of Jack's tunes contain elements of that rough spontaneity and stark emotion. And it's even more apparent when he performs live that he's channeling exactly what the blues mean to him. Since his own music has moved me so intensely, it's not surprising that I'm also moved by what inspires him. As a result, my own fast-growing collection of blues records runs straight through the heart of the Delta.

One thing that does surprise me, though, is that I've yet to find evidence that Jack's ever paid homage to one of the most hard-core Delta musicians of all-- Skip James. So my intro to Skip came via a detour from Jack to a record label run by Jimmy Danger, who once played in the band Henry & June with one of Jack's buddies (this digression isn't as aimless as it seems, as Jack has also covered H & J's Goin' Back to Memphis, which is a fantastic modern day blues tune). Danger Limited Records' Black Jesus 7" series was launched with a cover of Skip's Hard Time Killin' Floor Blues that blew me away. So much so that I contacted Jimmy to ask him about the song. Turns out Skip is one of his favorite bluesmen and his description intrigued the hell out of me--

There are many things that set him apart from his contemporaries. The main thing was his choice of tuning. He played primarily in an open D minor tuning. He was the only one at the time to adopt that style and there haven't been many to do it since. He was the master at it. The other often overlooked difference was his piano playing. He was just as good at piano as he was the guitar. His guitar songs are soo haunting. I think it is half the tone of his guitar and half the way he sang. His voice would be the third thing to make him so different. He sang in a high falsetto. If you buy anything by him make sure to pick up the 1931 Grafton Wisconsin sessions. It will change the way you hear the blues.

Well, I've yet to find a good copy of those Grafton sessions, but I did stumble upon another gem, one that hit me even harder once I learned the history behind it. The Biograph release of Hard Time Killin' Floor Blues was recorded in 1964, 20 or so years after the last time Skip had picked up a guitar, and after he'd been hospitalized for a horrendous case of cancer. He was rediscovered that year in a Mississippi hospital by a group of Washington, D.C. blues fans including John Fahey, who brought him to D.C. where he ended up again in the hospital. After more treatments, they eventually took him all the way to the Newport Jazz Festival, at which Skip's performance stood in stark contrast to that of previously rediscovered Mississippi John Hurt. But in between, they took time to record the set of tunes on the Hard Time Killin' Floor Blues collection. Two of those songs were specifically about Skip's time in that D.C. hospital, and they're two of the most heartbreaking songs I've ever heard---

Layin' sick, honey, on my bed

I'm layin' sick, honey, and on my bed

I'm layin' sick, honey, and on my bed

I used to have a few friends but they wished that I were dead

In awful pain and deep in misery

Awful pain and deep in misery

Awful pain and deep in misery

I ain't got nobody to come and see about me

And every dog, baby, got a day

And every dog, baby, got a day

Every dog, baby, got a day

But I said, "Please, ma'am, don't you treat me this-a way"

The doctor came, lookin' very sad

The doctor came, lookin' very sad

The doctor came, lookin' very sad

He diagnosed my case and said it was awful bad

He walked away, mumblin' very low

He said, "He may get some better but he'll never get well no more"

I've got a long trip and I'm just too weak to ride

I've got a long trip and I'm just too weak to ride

I got a long trip and I'm just too weak to ride

Now it's a thousand people standin' at my bedside

I hollered, "Lord, oh Lord, Lord, Lordy, Lord

Oh Lordy, Lord, Lord, Lord

I been so badly misused and treated just like a dog"

I ain't gonna cry no more

I ain't gonna cry no more

I ain't gonna cry no more

Cause down this road every traveler got to go

I been on the ocean, I been across the sea

Been on the ocean, I been across the sea

Been on the ocean, I been across the sea

I ain't found nobody would feel my sympathy

You take a stone, you can bruise my bone

You take a stone and you can bruise my bone

You take a stone and you can bruise my bone

But you sure gonna miss me when I'm dead and gone

In the hospital, now

In Washington D.C.

Ain't got nobody

To see about me

But I was a good man

But I was a poor man

You can understand

All the doctors

And nurses, too

They came and they asked me

'Who in the world are you?'

I says, I'm a good man

But I'm a poor man

You can understand

The doctors and nurses

They shakin' their head

Said, 'Take this poor man

And put him to bed'

Because he's a good man

We know he's a poor man

We can understand

I didn't go hungry

I had plenty to eat

I had good treatment

And a place to sleep

Because I was a good man

They knew I was a poor man

They could understand

I met a little damsel

She promised me

That she would love me

And always be sweet

She found out I was a poor man

And I thought I was a good man

She couldn't understand, no

Now, when she left me

She got in the door

She waved me, good-bye

I haven't seen her no more

She found out I was a good man

She knew I was a poor man

She couldn't understand

The doctors and nurses

They shakin' my hand

Say, 'You can go home now, Skip

You's a sound, well man'

Because you's a good man

You's a poor man

We can understand

I's thankin' my doctor

And I was shakin' his hand

I'm gone play these, 'Hospital Blues'

'Till you's a wealthy man'

You took me as a good man

You knew I was a poor man

You could understand

You know I was a good man

But I'm a poor man

You can understand

That, right there. That's what it is about the blues. Get it? Now see if you can get out.